Formant dynamics analysis: a worked example

Tutorial

The acoustic analysis of vowels, as far as monophthongs are concerned, has been based on a rather uncontroversial procedure for many decades: compute the centre frequency of the first formant (F1) e.g. at temporal midpoint, repeat the process for the second formant (F2), and then plot the vowels as single points in the F1/F2 plane. But a recurring question I get from students and colleagues is: how do I analyze non monophthongs acoustically (i.e. formant dynamics)?

This is slightly more complex for a number of scientific and technical reasons: formant contours come in different sizes, which is hard to handle in flat files (e.g. spreadsheets) and implies choices in terms of temporal alignment, time normalization or warping; coming up with a parsimonious set of parameters to describe a contour requires techniques that phonetics students may not be familiar with, etc.

Over the years, I’ve used different techniques like:

- locating two ’targets’ within a single vowel, and plotting two points, joined by a straight line, in the F1/F2 plane;

- fitting lines or curves (e.g. polynomial regression) to formant contours and using the coefficients in the equations as parameters for the analysis;

- computing the distance travelled in the F1/F2 plane.

Today I’d like to show a full worked example involving the discrete cosine transform with R software. I’ll focus on the practical aspects, leaving out the scientific rationale (see e.g. Elvin et al., 2016). And I’m providing the dataset: it consists of 360 vowels (12 speakers × 10 words × 3 repetitions) that were collected in Glasgow to study the effect of a morphologically-conditioned vowel alternation (stemming from the so-called Scottish Vowel Length Rule – see e.g. Ferragne, 2020) on formant trajectories. These vowels occur in minimal pairs like tide-tied; the heteromorphemic [d] in the second word causes the preceding vowel to lengthen and to display a different formant pattern from the monomorphemic item.

Now moving on to the tutorial itself…

Download the dataset here, and open it in R (I use RStudio): File > Open file… This creates a new variable in the workspace, called dataList.

Additional packages are required; you should install dtt, ggplot2 and reshape2 before doing anything else.

#you can install them all at once

install.packages(c("dtt", "ggplot2", "reshape2"))

Here’s how you can access the data stored in the list:

#show metadata for 3rd object in the list

dataList[[3]]$metadata

#show 3rd word

dataList[[3]]$metadata$word

#show F1 contour for the 3rd item

dataList[[3]]$data$F1Hz

#show F2 contour for the 5th item

dataList[[5]]$data$F2Hz

#etc...

Next we retrieve the list of speakers and words, and create a new factor with 2 levels: “L” if the vowel is long, and “S” if it’s short:

#get list of words

wordList = unlist(lapply(dataList, function(x) x$metadata$word))

#get speaker list

speakerList = unlist(lapply(dataList, function(x) x$metadata$speaker))

#create new variable to distinguish short and long vowels

vowelType = matrix(nrow = length(wordList), ncol = 1)

vowelType[wordList %in% c("bide","pride","ride", "side", "tide")] = "S"

vowelType[!(wordList %in% c("bide","pride","ride", "side", "tide"))] = "L"

vowelType = as.factor(vowelType)

Interpolation is then performed so that, whatever its initial duration, a contour is now represented by 30 equally-spaced points. This is standard in the literature though to me, it’s only partially valid… but that’s another story…

#perform cubic spline interpolation

mySpline.F1 = lapply(dataList, function(x) spline(x$data$F1Hz, n= 30))

mySpline.F2 = lapply(dataList, function(x) spline(x$data$F2Hz, n= 30))

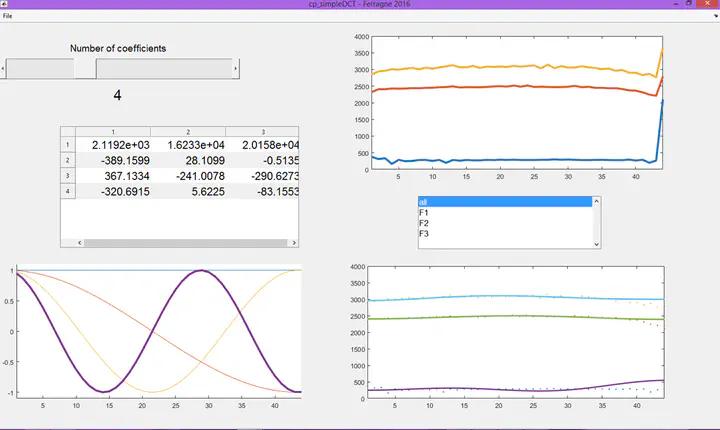

And here the DCT is computed:

#compute DCT coefficients

require(dtt)

myDct.F1 = lapply(mySpline.F1, function(x) dct(x$y))

myDct.F2 = lapply(mySpline.F2, function(x) dct(x$y))

#keep only first 3 coefficients

coef3.F1 = lapply(myDct.F1, function(x) {x[4:length(x)]= 0; x})

coef3.F2 = lapply(myDct.F2, function(x) {x[4:length(x)]= 0; x})

#compute inverse transform

inv.F1 = lapply(coef3.F1, function(x) dct(x, inverted = T))

inv.F2 = lapply(coef3.F2, function(x) dct(x, inverted = T))

#store coefficients to data frame (here only F1; but it works for F2 too)

coefMat.F1 = matrix(unlist(lapply(coef3.F1, function(x) {x[1:3]})), nrow = length(coef3.F1), byrow = T)

scatterData = data.frame(speakerList, wordList, vowelType, coefMat.F1)

colnames(scatterData) = c("speaker", "word", "length","c0", "c1", "c2")

#get mean of 3 word repetitions for each speakers

meanCoefs = aggregate(cbind(c0,c1,c2)~speaker + word + length, scatterData, mean)

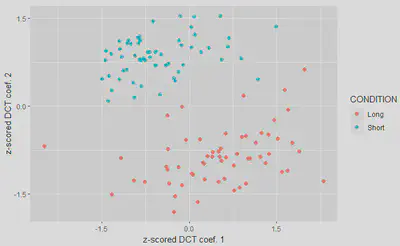

Here the DCT coefficients are z-scored. You could skip this step; I tend to z-score most values related to vowel formants because their frequencies are partly speaker-dependent.

#scale coefs by speaker

sortedCoefs = meanCoefs[order(meanCoefs$speaker),]

mySpeakers = unique(meanCoefs$speaker)

scaledCoefs = data.frame(matrix(nrow = dim(meanCoefs)[1], ncol = dim(meanCoefs)[2]-3))

for (spk in 1:length(mySpeakers)){

currentData = sortedCoefs[sortedCoefs$speaker == mySpeakers[spk],4:dim(meanCoefs)[2]]

scaledCoefs[sortedCoefs$speaker == mySpeakers[spk],] = scale(currentData)

}

scaledCoefDf = data.frame(sortedCoefs$speaker, sortedCoefs$length, scaledCoefs)

colnames(scaledCoefDf) = c("speaker", "length", "c0", "c1", "c2")

levels(scaledCoefDf$length) = c("Long", "Short")

Final step: plot the results:

#do scatterplot

require(ggplot2)

ggplot(scaledCoefDf, aes(c1, c2, col = length)) +

geom_point(size = 2) + xlab("z-scored DCT coef. 1") +

ylab("z-scored DCT coef. 2") + scale_y_continuous(breaks=seq(-1.5,1.5,1.5)) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks=seq(-1.5,1.5,1.5)) + coord_fixed() +

guides(color=guide_legend("CONDITION"))

You should get something like this:

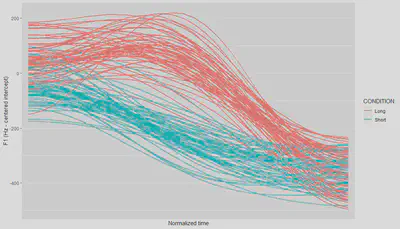

And optionally, if you want to see what the inverse DCT (the smoothed version of the original curve reconstructed from the first 3 coefficients) looks like, here’s my suggestion:

require(reshape2)

smoothMat = matrix(unlist(inv.F1), nrow = length(coef3.F1), byrow = T)

smoothDF = data.frame(speakerList, wordList, vowelType, smoothMat)

colnames(smoothDF) = c("speaker", "word", "condition", 1:30)

#create grouping factor

groupFact = paste0(speakerList, wordList, vowelType)

smoothDF$grouping = groupFact

#compute mean curves per word per speaker

meanCurves = aggregate(.~speaker + word + condition + grouping, smoothDF, mean)

#do by-speaker data centering

mySpeakers = unique(meanCurves$speaker)

centeredData = data.frame(matrix(nrow = dim(meanCurves)[1], ncol = dim(meanCurves)[2]-4))

for (spk in 1:length(mySpeakers)){

currentData = meanCurves[meanCurves$speaker == mySpeakers[spk],5:dim(meanCurves)[2]]

currentMean = colMeans(currentData)[1]

centeredData[meanCurves$speaker == mySpeakers[spk],] = currentData - currentMean

}

centerCurvDF = data.frame(meanCurves$speaker, meanCurves$word, meanCurves$condition,

meanCurves$grouping, centeredData)

colnames(centerCurvDF) = c("speaker", "word", "condition", "grouping", 1:30)

levels(centerCurvDF$condition) = c("Long", "Short")

meltCenterDF = melt(centerCurvDF, variable.name = "timeStep")

ggplot(meltCenterDF, aes(timeStep, value,

colour = condition,

group = grouping)) + geom_line(size=.8) +

xlab("Normalized time") +

ylab("F1 (Hz - centered intercept)") +

guides(color=guide_legend("CONDITION")) +

scale_x_discrete(breaks = NULL)

Quick edit (2022-07-15):

I wrote this tutorial 2 years ago and the whole workflow is still working. However, I’ve just run into a minor issue today with the following error message: “‘Rcpp_precious_remove’ not provided by package ‘Rcpp’”

I re-installed and loaded Rcpp explictly:

install.packages('Rcpp')

library(Rcpp)

And everything worked nicely again! If you have trouble reproducing my tutorial, please don’t hesitate to [contact me](mailto:emmanuel.ferragne@u-paris.fr?subject=dynamic formant tutorial).

End of edit

Once you master the procedure, you’ll be ready to apply it to your own data. The easiest way to have the right structure for you dataset is to perform your formant analysis following the workflow I describe here.

REFERENCES

Elvin, J., Williams, D., & Escudero, P. (2016). Dynamic acoustic properties of monophthongs and diphthongs in Western Sydney Australian English. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 140(1), 576-581)

Ferragne, E. (2020). The production and perception of derived phonological contrasts in selected varieties of English. In A. Przewozny, C. Viollain, & S. Navarro, The Corpus Phonology of English: Multifocal Analyses of Variation (p. 30-49). Edinburgh University Press.