Recent & Upcoming Talks

2026

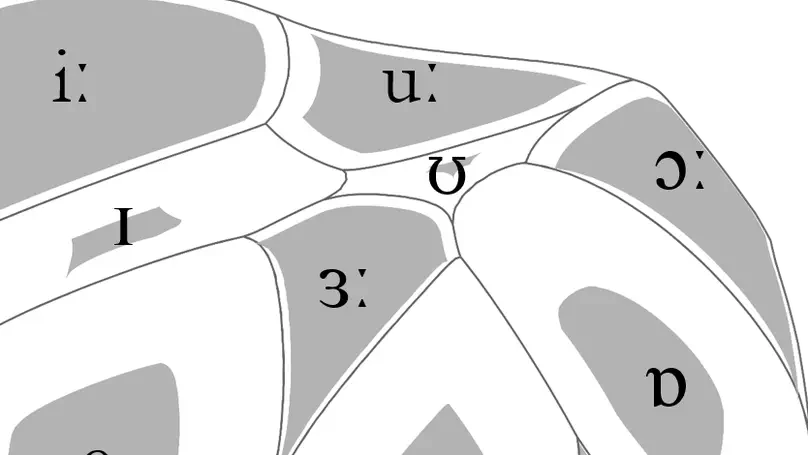

The PARAAF (Perception de l’Anglais et Reconnaissance Automatique d’Accents à la Fac) corpuswas created at the Université Paris Cité in November and December 2024. It consists in read speechrecorded by 431 students from the Licence LLCER ´Etudes anglophones.The corpus includes sentences and word lists in English and in French that were chosen tostudy different variables. The sentences were created to focus on the differences between BritishEnglish and American English. The word lists include the /hVd/ words already present in theexisting literature on English vowels. Each word list was repeated three times while the sentenceswere only recorded once. Half the participants started with the English part of the corpus and theothers read the French part first.The metadata contains the participants’ sexes, their birthdates, their regions of origin, their agewhen they started learning English, the languages they speak, their university level, the languagein which they started the recording, which recording booth they were in, and the names of theexperimenters who took care of them.After giving a summary of the metadata, we shall present a study of how French learnerspronounce the non-native contrast /i:/-/ɪ/. We measured vowel duration as well as vowel overlapwith Pillai scores in order to analyse their acquisition of L2 phonological categories. Results showedthat the participants did not produce a significant duration difference between /i:/ and /ɪ/, and thattheir realisations of these vowels tended to overlap in the acoustic space. We found varying degreesof acquisition as Pillai scores range from nearly complete overlap to nearly perfect separation,and duration differences from low to very high (nearly exaggerated when compared to nativemeasurements). The implications of these results will be discussed further in our presentation.

Abstract A central theoretical issue in sociophonetics concerns the relationship between group-level and individual variation (Kendall et al., 2023; Walker and Meyerhoff, 2013). While variationist research has traditionally focused on socially defined speaker groups, more recent third-wave approaches place the individual at the forefront, viewing speakers as stylistic agents who use linguistic features in context as resources for identity construction (Eckert, 2012).

This study investigates the perception of the flapped allophone of /t/ in British English, a feature traditionally associated with American English. We explore whether this perception has evolved among British English speakers. Using an identification perception experiment, participants from two age groups (18-25 and 55+) had to identify the orthographic representation of the audio stimuli of nonce words containing a flap /t/, produced by speakers of SBE and GA. Preliminary analysis revealed that while the effect of generation alone was not significant, the interaction between generation and accent was significant. Younger participants were more likely to correctly identify a flap in British English compared to older participants, suggesting a generational shift in the perception of this phonetic feature. These findings indicate a potential evolution in the acceptance of flapped /t/ as a variant in British English, which may be due to the prevalent use of American English in popular media.

2024

Si notre habitude de collecter des données authentiques, de les organiser de façon rationnelle et de les partager avec nos pairs a probablement fait progresser la recherche ces dernières décennies, il nous faut cependant rester humbles quant à ce qu’un corpus peut nous apprendre. D’abord, la linguistique dite « de corpus » cultive parfois une fascination pour les phénomènes attestés, nous conduisant ainsi à négliger ceux qui ne le sont pas. Or, comme Bloomfield dans ses postulats, je crois que c’est l’ensemble des possibles qui nous intéresse dans l’étude du langage humain, et pas seulement celui des phénomènes effectivement constatés. Ensuite, il arrive qu’à trop vouloir se focaliser sur les données, on oublie de formuler explicitement des prédictions en amont d’un travail empirique. Or, et a fortiori quand on réutilise un corpus collecté pour d’autres besoins (l’open data n’a pas que des avantages), le risque d’aboutir à de fausses interprétations ex post facto n’est pas négligeable. Le monde grouille en effet de corrélations fortuites ; ce n’est pas un hasard si les philosophes des sciences, comme Popper dans sa méthode hypothético-déductive, insistent sur la préséance de la formulation d’une hypothèse sur le test empirique ad hoc de celle-ci. Enfin, si, comme le proposent les modèles usage-based, nos représentations sont le résultat d’un apprentissage statistique qui garde une trace détaillée de tout ce que nous avons été amenés à entendre, alors sonder ce « corpus mental » – pour reprendre l’expression du linguiste John R. Taylor – au moyen de méthodes éprouvées en psycholinguistique et neurosciences permet sûrement d’aller au-delà de simples enregistrements audio du corpus phonétique/phonologique typique. Les 25 années que je viens de passer à faire de la phonétique m’ont conduit à une très nette préférence pour les approches expérimentales par rapport à la réutilisation de corpus préexistants ou l’enregistrement de données audio suivant un protocole qui n’aurait pas été spécialement conçu pour ma question de recherche. A l’aide d’exemples, et notamment des limites constatées dans ma propre recherche, j’espère montrer ce qui m’a conduit à préférer l’expérimentation.

2023

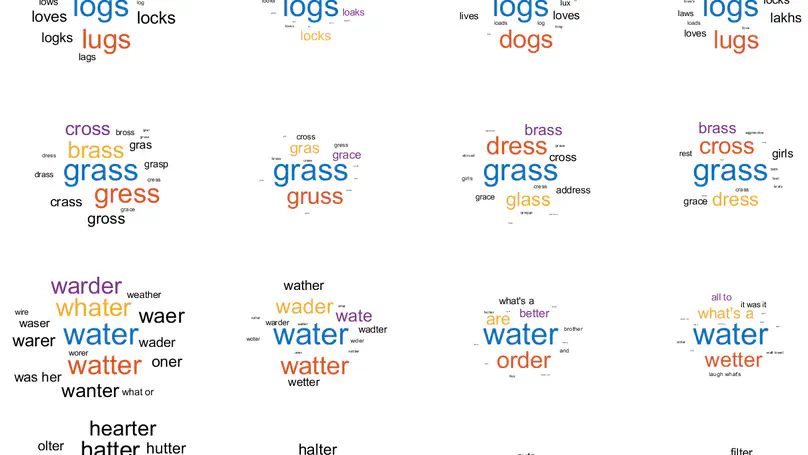

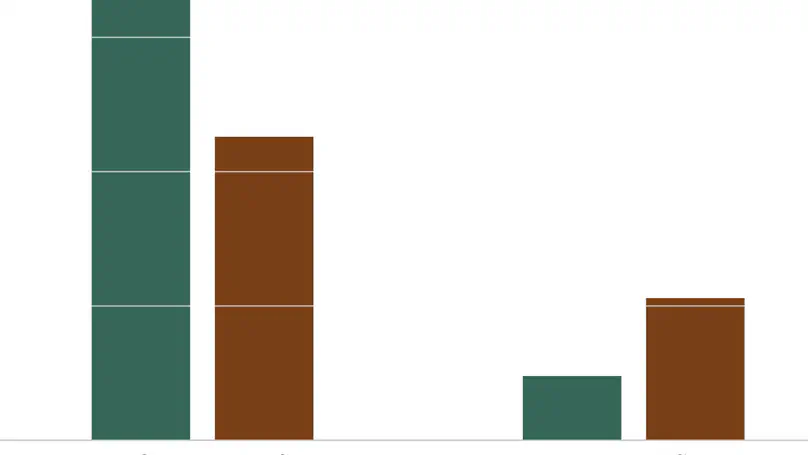

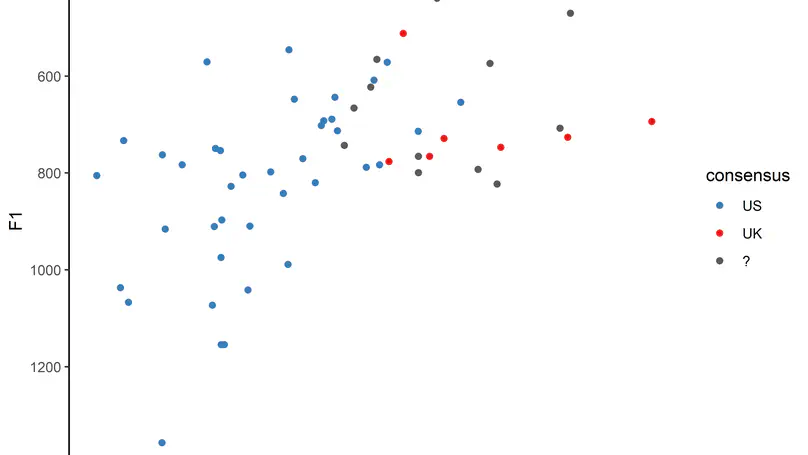

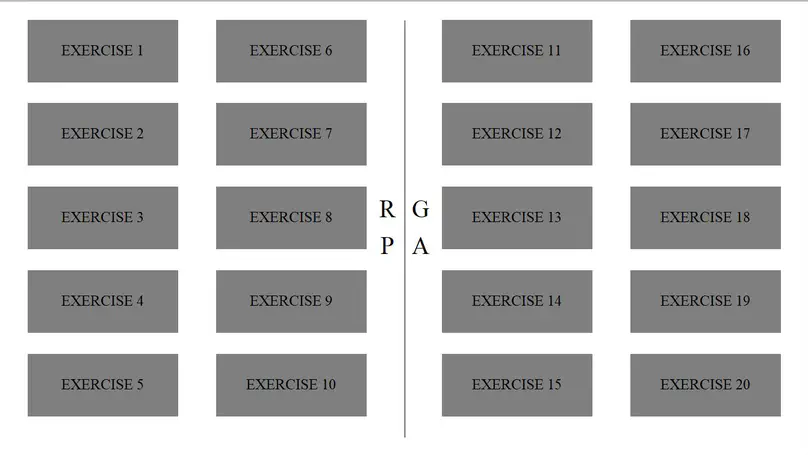

Students in English Studies departments in France are expected to target a restricted set of native accents (either Received Pronunciation – RP – or General American – GA). We recorded 307 students who read phonetically-rich sentences specially designed to elicit accent-specific pronunciation features. We listened to these specific features, ran automatic speech recognition, and performed automatic accent classification. We examined to what extent we, the listeners, agreed with one another, what insight could be gained from automatic speech recognition and accent classification, and whether our perception concurred with automatic methods. Among other things, our results show that only 7% of our students use one of the two native models consistently, with two thirds favouring the American model.

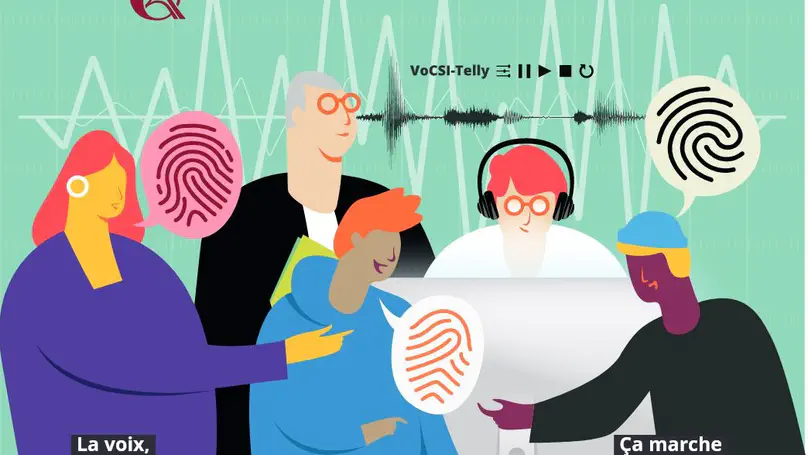

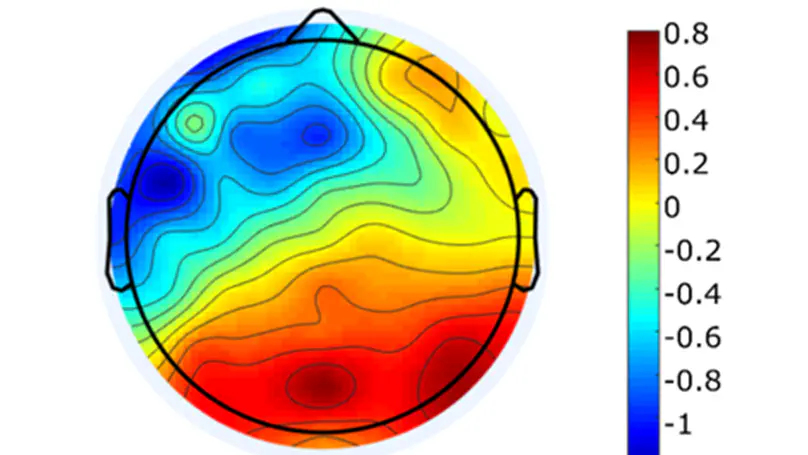

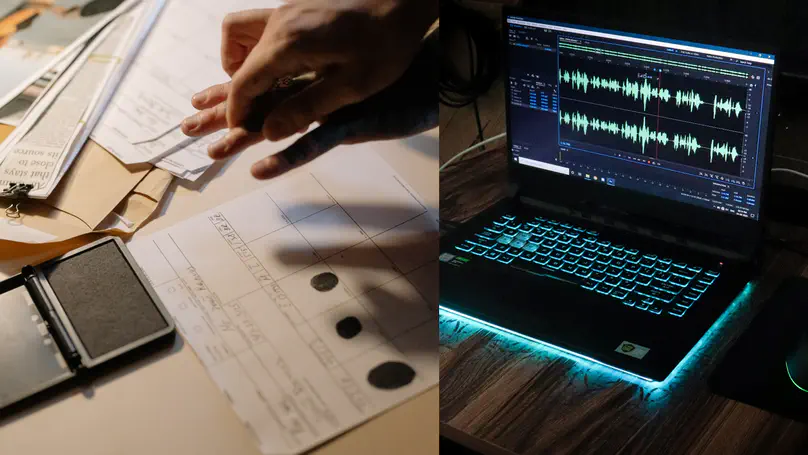

La voix humaine ne peut pas être assimilée à des indices véritablement biométriques comme les traces papillaires ou l’ADN. Cependant, notre expérience quotidienne tend à nous faire penser le contraire puisque nous nous appuyons spontanément sur la voix d’un individu pour confirmer son identité. La tension entre science et croyance populaire est donc très marquée. Cette tension nous est régulièrement retransmise par les média qui couvrent les rares procès où la voix des personnes mises en causes occupe une place centrale. Après plusieurs décennies émaillées de controverses, l’expertise vocale en criminalistique se construit aujourd’hui dans une dynamique plus apaisée. Elle bénéficie entre autres de la mise en place d’un dialogue fécond entre universitaires et laboratoires des forces de l’ordre encouragé par l’obtention de projets financés communs. Après un rappel du contexte entourant l’application des méthodes de comparaison de voix en criminalistique, je présenterai les trois volets de mon implication récente dans des collaborations avec le Service National de Police Scientifique : 1) la caractérisation phonétique acoustique de la variation inter-individuelle au moyen de réseaux de neurones artificiels, 2) le décryptage des clichés sur l’expertise vocale véhiculés par les séries policières et 3) l’étude des stéréotypes liés à l’accent d’un individu par le biais de potentiels évoqués en EEG.

2022

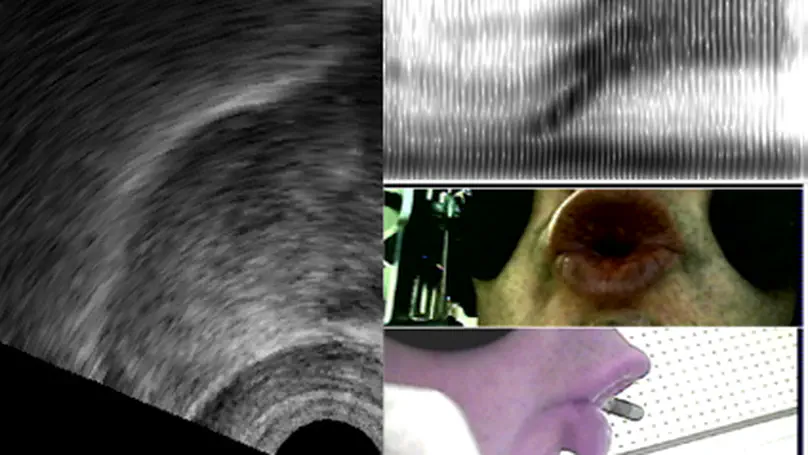

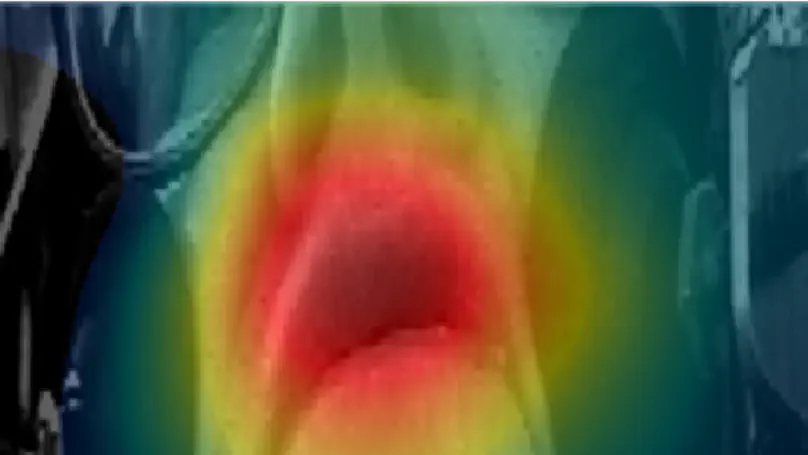

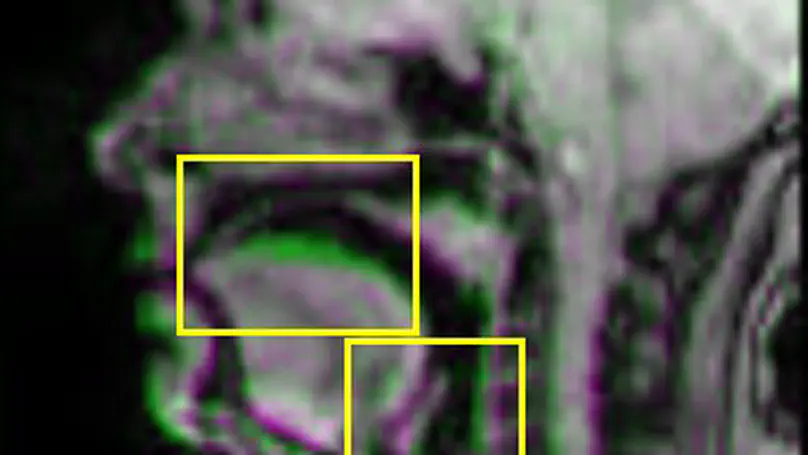

Des réseaux de neurones convolutifs ont été entraînés sur des spectrogrammes de voyelles /ɑ̃/ et de séquences aléatoires de 2 secondes extraites de 44 locuteurs du corpus NCCFr afin d’obtenir une classification de ces derniers. Ces deux modèles présentent une répartition équivalente des locuteurs dans l’espace acoustique, ce qui suggère que la classification a été faite sur des critères indépendants des phonèmes précis extraits. De multiples mesures phonétiques ont été effectuées afin de tester leur corrélation avec les représentations obtenues : la f0 apparait comme le paramètre le plus pertinent, suivie par plusieurs paramètres liés à la qualité de la voix. Des zones d’activation (Grad-CAM : Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) ont été calculées a posteriori afin de montrer les zones spectrales et temporelles utilisées par le réseau. Une analyse quantitative de ces cartes d’activation a donné lieu à des représentations des locuteurs qui ne sont pas corrélées aux mesures phonétiques.

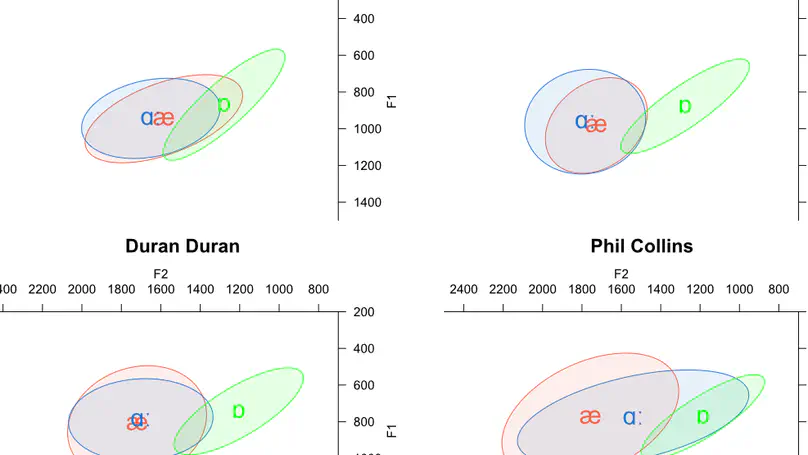

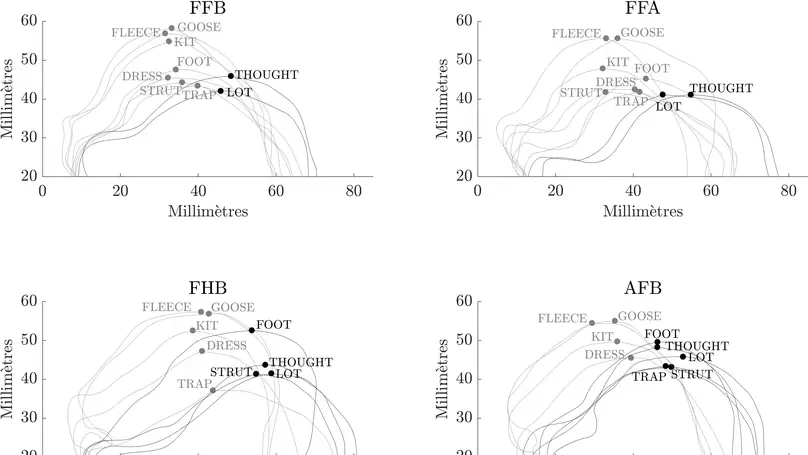

S’inscrivant dans la lignée de Trudgill (1983), cet article vise à comprendre le phénomène d’américanisation de la prononciation dans la voix chantée des artistes britanniques des années 1980. Le Heavy Metal a été sélectionné comme genre musical typiquement britannique à son origine, et étudié à l’aune de deux points de référence : la pop britannique et la pop américaine. Les voyelles de TRAP-BATH et LOT, dont les réalisations divergent entre les deux variétés d’anglais (britannique et américaine), ont fait l’objet d’analyses acoustiques chez six artistes. Nos résultats montrent qu’il existe un certain degré d’américanisation dans les productions chantées des artistes britanniques, qui est cependant plus marqué chez les groupes de Heavy Metal que chez les chanteurs de pop. La Discussion revient sur les divers types de paramètres (sociophonétiques, articulatoires, etc.) qui contraignent ce phénomène d’américanisation, et analyse la fiabilité des mesures acoustiques (formants et MFCC) calculées.

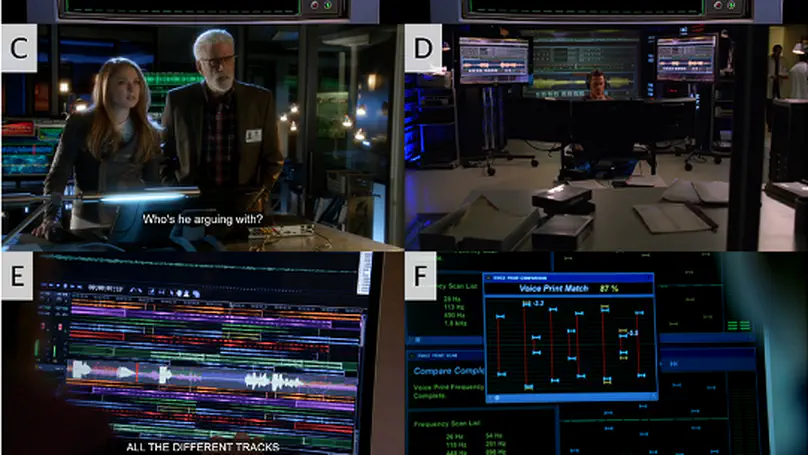

À travers le prisme pluridisciplinaire de la phonétique, du traitement du signal et des études visuelles, et sous l’œil des experts de la police scientifique, nous avons analysé plus d’une centaine de scènes de séries américaines impliquant une expertise du signal audio et, en particulier, de la voix. Nous tentons d’identifier des schémas récurrents qui contribuent à entretenir certains mythes liés à l’identification d’un individu par sa voix. Nous évaluons le degré de plausibilité de certains extraits et proposons les prémisses d’une esthétique de l’expertise vocale. Nous souhaitons ainsi mieux comprendre comment le grand public se représente les applications criminalistiques des sciences de la parole et espérons, en confrontant la fiction à la réalité, faire passer un message pédagogique à destination non seulement des téléspectateurs, mais également des professionnels de la police et de la justice.

14h00 : Introduction par Emmanuel Ferragne et Laurianne Georgeton Communications orales 14h10 : Voir le son, écouter l’image par Martine Beugnet, Margaux Cecchini, Emmanuelle Delanoë-Brun et Anne Guyot-Talbot 14h30 : Perturbation du débit et reconnaissance des voix par Christine Meunier, Benjamin O’Brien et Alain Ghio

Cette conférence s’attaque au mythe de l’empreinte vocale tel qu’il est représenté à l’écran. Des spécialistes de l’étude des séries, de l’analyse de la parole, ainsi que les experts de la police scientifique, décryptent la mise en scènce de la comparaison de voix et confrontent la fiction à la réalité.

2021

Si parler anglais avec une syntaxe imprécise et un lexique lacunaire constituent un frein évident à des opportunités de carrière internationale, l’impact de la prononciation ne doit cependant pas être sous-estimé.

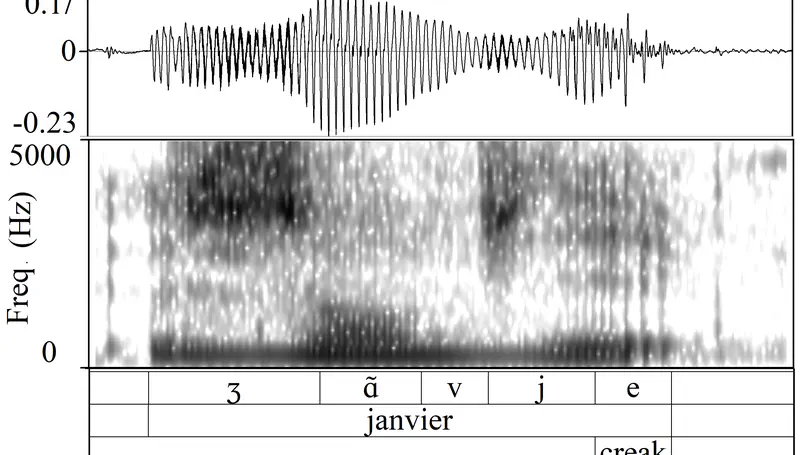

Voice quality is known to be an important factor for the characterization of a speaker’s voice, both in terms of physiological features (mainly laryngeal and suprala-ryngeal) and of the speaker’s habits (sociolinguistic factors). This paper is devoted to one of the main components of voice quality: phonation type. It proposes neural representations of speech followed by a cascade of two binary neural network-based classifiers, one dedicated to the detection of nonmodal vowels and one for the classification of nonmodal vowels into creaky and breathy types. This approach is evaluated on the spontaneous part of the PTSVOX database, following an expert manual labelling of the data by phonation type. The results of the proposed classifiers reach on average 85 % accuracy at the frame-level and up to 95 % accuracy at the segment-level. Further research is planned to generalize the classifiers on more contexts and speakers, and thus pave the way for a new workflow aimed at characterizing phonation types.

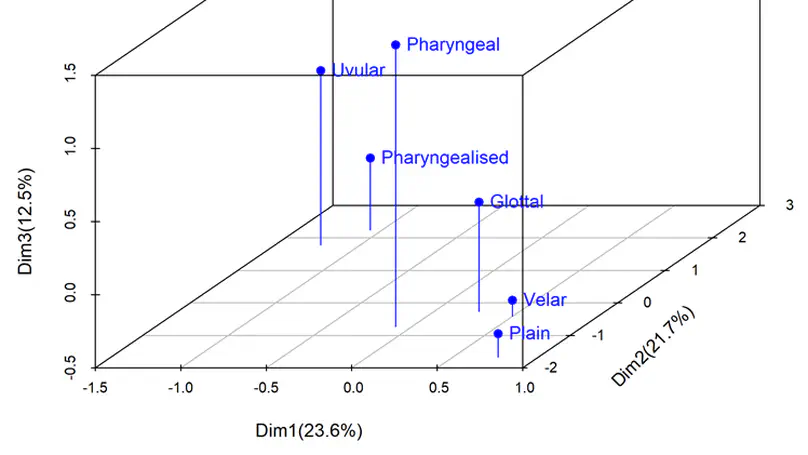

Since scientists’ individual epistemological preferences infallibly shape the output of their research, this thesis starts with a presentation of the author’s position with respect to a number of methodological issues pertaining to the field of contemporary phonetics. Such concepts as corpora, experimental techniques, quantitative methods, and the role of technology are discussed with the aim of making the author’s scientific values and biases more explicit. The following chapters offer a selection of research works the author has carried out since his PhD in 2008. They show an evolution from corpus-based acoustic phonetics to more experimental protocols involving a great diversity of instruments and data types. From the automatic classification and acoustic-articulatory description of British Isles accents to the development of the gradient phonemicity hypothesis; from the study of speech rhythm to psycholinguistic experiments with French learners of English, the thesis covers the main findings and highlights how this wide array of interests and methods has served two consistent goals: an agnostic approach to new puzzles, and the possibility to efficiently help students develop their own scientific identity. The final part of the thesis addresses the forthcoming paradigm shift that deep learning will bring about in many academic fields with illustrations from the author’s recent work.

2020

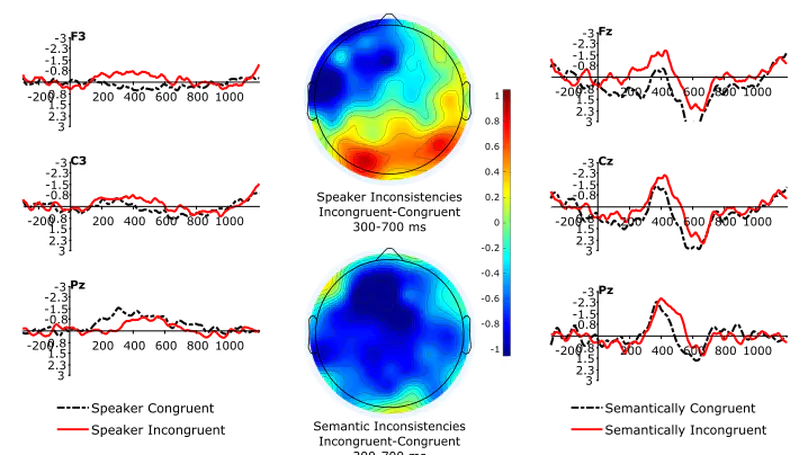

En criminalistique, la comparaison de voix consiste à déterminer si deux enregistrements vocaux émanent d’un même individu ou non. Notre objectif dans le cadre du projet ANR VoxCrim (en cours) vise à établir une norme certifiée définissant les conditions nécessaires à l’application d’un protocole étalonné dans ce domaine. Au-delà des éléments très techniques de modélisation acoustique (que je ne développerai pas ici), on relève au moins deux aspects qui influencent la perception d’une expertise vocale : 1) la représentation des technologies de la parole dans la conscience collective – qu’on sait très dépendante des séries télévisées – et 2) les stéréotypes liés à la voix d’un individu. C’est ce dernier point qui constitue le cœur de ma présentation. Nous avons récemment réalisé une étude en électroencéphalographie avec la technique des potentiels évoqués dans le but de mettre en évidence les attentes générées dans l’esprit des auditeurs par un accent socialement marqué. Lorsque le contenu sémantique d’un énoncé n’est pas congruent avec ces attentes stéréotypées, un effet N400 a pu être mis en évidence. Il apparaît donc que l’activation de stéréotypes liés aux accents s’effectue dans un temps extrêmement court et semble relever des mêmes mécanismes que ceux qui régissent le traitement lexico-sémantique.

2019

Somebody’s pronunciation says a lot about who they are: geographical origins, education level, or socioeconomic background. The way we speak contains a great deal of information about our identity and how we present ourselves to the rest of the world. This observation does not only apply to speaking; it also holds true for singing. In 1983, sociolinguist Peter Trudgill published a study entitled Acts of Conflicting Identity: the sociolinguistics of British pop-song pronunciation, in which he identified a tendency for British pop artists like The Beatles to adopt an American-like pronunciation when singing. He concluded that this Americanization in songs by British artists was a consequence of the American domination of the music industry at that time, because it seemed appropriate for artists to sound American when performing a predominantly American activity. The aim of this study is to see whether this principle applies to Heavy Metal in its original form as a distinctly British genre. Indeed, Heavy Metal was born out of the daily struggles of Northern England’s working class youth facing de-industrialization in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and can thus be considered emblematic of a particular Northern British and more generally British identity. To study whether British Heavy Metal has followed the popular pattern of Americanization, or if it has maintained its British roots in terms of pronunciation, we analyzed sung and spoken productions by two British Heavy Metal bands: Iron Maiden and Def Leppard. We focused on two pronunciation features that distinguish Northern British English from Southern British English and in turn, Southern British English from American English. The first one relates to the pronunciation of the two types of vowels found in words such as foot (/ʊ/) and strut (/ʌ/), and is technically referred to as the FOOT-STRUT Split. The second pronunciation feature we looked at concerns the consonant /t/ when found in the middle of a word, such as in water, atom or better. In American English, this /t/ is pronounced in such a way that it sounds more like a /d/. This process is known as T Voicing and is one of the main distinguishing characteristics between British and American English. The following questions were thus addressed: 1. Based on analyses of the FOOT-STRUT Split and T Voicing, do Iron Maiden and Def Leppard show a tendency to Americanize their pronunciation in their sung productions? 2. If so, what are the factors influencing this preference? Is it only a question of imitation as Trudgill suggests or do other factors come into play?

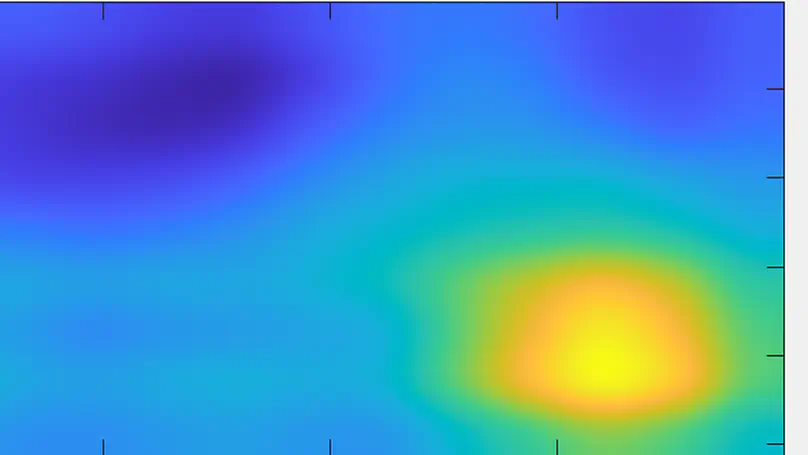

Modern phonetics has relied, to a large extent, on researchers’ ability to extract patterns from visual representations of speech. In this respect, if linguists were medical doctors, phoneticians would be radiologists. Speaking of radiologists, recent progress in artificial intelligence has made it possible for certain deep learning algorithms to outperform human pathologists at detecting abnormalities in medical images (Litjens et al., 2017). If the analogy holds, it is fair to ask whether artificial intelligence can beat phoneticians at their own game or, at least, constitute a significant addition to their toolbox. My contention is that the advent of deep learning opens up a whole new research programme for the humanities in general, and phonetics in particular. While deep neural networks (DNNs) have been duly praised for bringing about a major breakthrough in applied fields like automatic speech (Hinton et al., 2012) or image (Simonyan & Zisserman, 2015) recognition, we are only just starting to realize how fundamental research in our field can benefit from them (Ferragne et al., 2019; Pellegrini & Mouysset, 2016). There are at least three reasons why DNNs will trigger a paradigm shift in phonetics. Firstly, unlike other quantitative techniques, DNNs can extract relevant representations from the speech signal without the need for a human expert to provide the system with hand-picked features (Goodfellow et al., 2016, for a comprehensive account of DNN properties). As a result, typical workflows now boast improved reproducibility; the possibility is raised that previously unnoticed parameters can be brought to light; and manual segmentation – a major bottleneck in phonetic analysis – is no longer needed in some cases. Secondly, deep learning will contribute to bringing the old parsimony-driven paradigm to a close. There is a whole record of experimental research that demonstrates that mental phonetic representations are detailed and multidimensional (Pierrehumbert, 2016). So, now that the high-dimensionality taboo has been broken, and that increasingly powerful and cheap computing resources have become available, the time is just right for the emergence of DNNs in phonetics, with their rich inputs and outputs. Thirdly, the current focus on explicability in the deep learning community has led to effective methods to visualize what DNNs learn (Chattopadhay et al., 2018). My claim here is that scientific findings based on visuals are key to bridging the divide between the hard sciences and humanities. And “visible speech”, the powerful synaesthetic cornerstone of contemporary phonetics, is more than ever legitimatized by DNN-based methods. Moreover, such techniques undoubtedly represent the logical alternative to the modern unreasonable urge to (over-) use inferential statistics and its misleading probability values. I will illustrate these claims with examples taken from on-going work in this nascent research field. I will more specifically focus on how convolutional neural networks used in image recognition and computer vision can be adapted to the study of phonetics. I will discuss the advantages and shortcomings of this novel approach, and I hope to show that while deep learning lies at the intersection of experimental and corpus phonetics, it offers the best of both worlds.

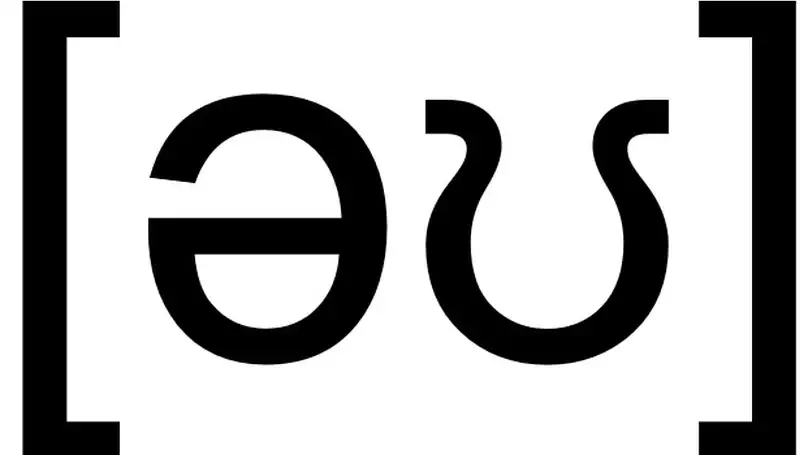

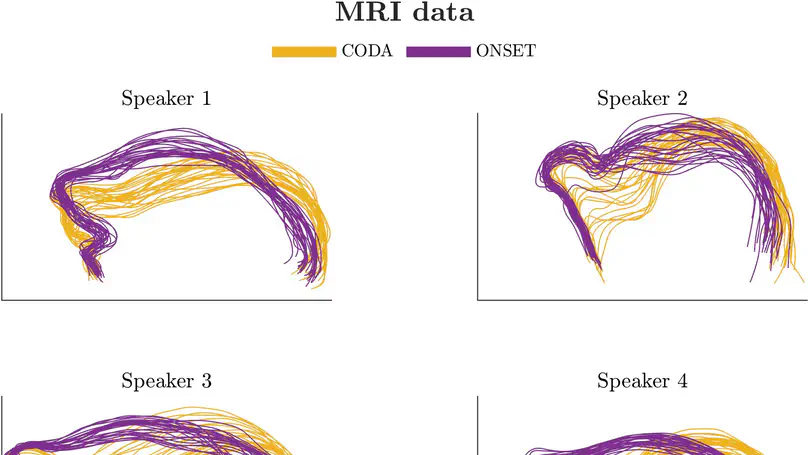

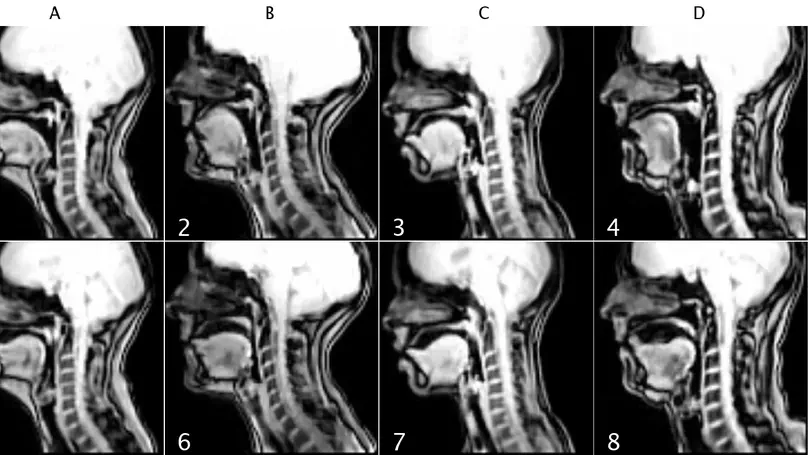

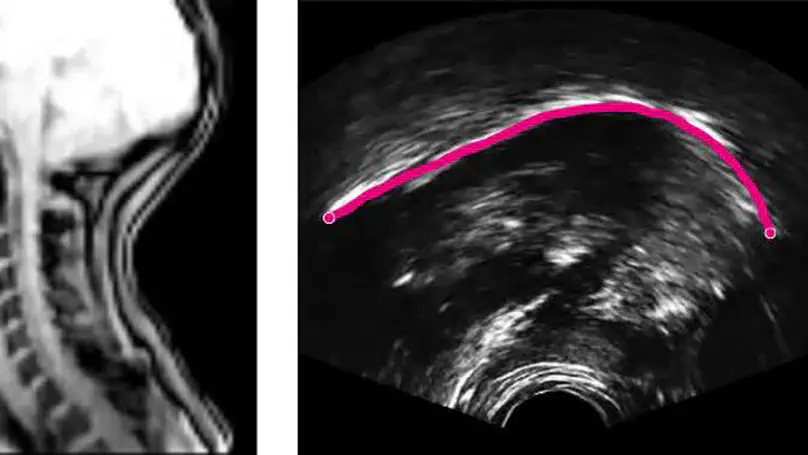

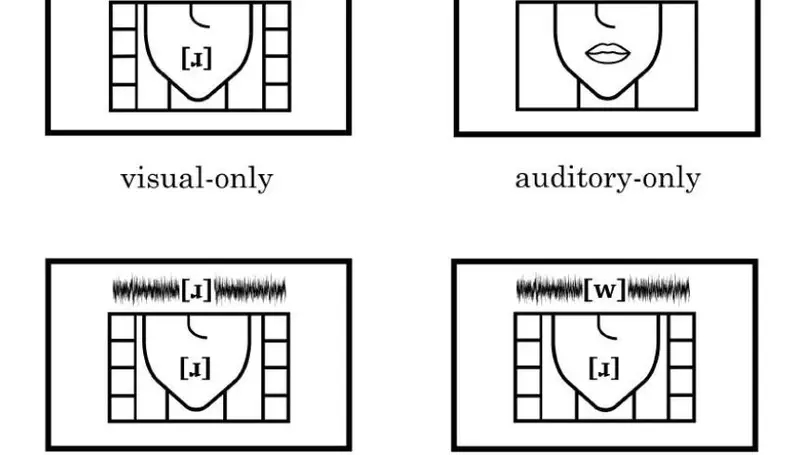

![[ɹ], [w] or [ʁ]: Investigating French advanced learners' productions of English /r/](/talk/%C9%B9-w-or-%CA%81-investigating-french-advanced-learners-productions-of-english-/r/featured_huf04e41ab7ab5b8c501a055280a804cf2_38383_808x455_fill_q75_h2_lanczos_smart1.webp)

![Me[t]al or Me[ɾ]al? The Role of Duration and Lexical Frequency on /t/ Flapping in the Singing Voice](/talk/metal-or-me%C9%BEal-the-role-of-duration-and-lexical-frequency-on-/t/-flapping-in-the-singing-voice/featured_hu06c6b10bf9d52a2986b5de5bfdaffa80_90388_808x455_fill_q75_h2_lanczos_smart1.webp)